Roving Periscope: Monsoon catastrophe threatens Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan

Virendra Pandit

New Delhi: The incessant, two-month-long devastating monsoon rains in Pakistan have not only submerged a third of the South Asian country under water, destroyed nearly 80 percent of food grain and farms, and drove 33 million people into misery, but they also damaged the ancient Indus Valley Civilization site of Mohenjo-Daro in the Sind Province.

On the right bank of the mighty Indus River, the site did not flood but still sustained damage from the torrential downpours. The media reported on Tuesday that the nearby farmers were pumping out flood water from their fields into the archaeological site.

The area around the ruins of Mohenjo–Daro received record rains, measured at 779.5mm, from August 16 to 26, considerably damaging the site. So much so that Mohenjo-Daro may even lose its world heritage tag if Islamabad fails to conserve and restore it urgently.

So attached is India to this site that, even after 75 years of losing it to Pakistan, a Hrithik Roshan-starred film, Mohenjo-Daro, hit the theatres in 2016. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB)’s logo also came from the Bull of the Indus Valley Civilization, which worshipped it for its fecundity.

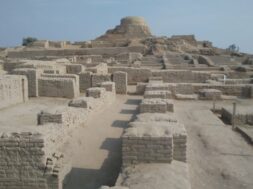

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) had, in 1980, declared Mohenjo-Daro a World Heritage Site. Developed around 2500 BC, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization, also known as Harappan Culture, with great urban planning features like standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems.

Mohenjo-Daro was abandoned in the 19th century BC as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and it remained undiscovered until the 1920s.

According to reports, Pakistan’s Department of Archaeology warned that UNESCO might remove it as a World Heritage Site if the government failed to urgently start conservation and restoration work at Mohenjo-Daro.

The area around Mohenjo-Daro received record rains for several days in August, resulting in considerable damage to the site and partial falling of several walls.

Pakistan’s daily Dawn reported that the curator of Mohenjo-Daro had, in his August 29 letter to his higher-ups, said his department was attempting to protect the site, but other departments — irrigation, roads, highways, and forest—did not do their duties.

He urged these departments to start the immediate repair of the bund, breached canal dykes, and removal of pipes. After his pleas, they started some emergency preservation work.

Some workers at the Mohenjo-Daro ruins were seen fending off rainwater seeping in and carving channels into this archaeological site. They tried to pump out stagnant water from excavated trenches at Mohenjo-Daro and scrambled to reinforce the retaining wall of the mound. On August 28, the ‘Mound of the dead,’ one of the site’s most iconic features, was seen covered in tarpaulin.

Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro were first recognized in 1922, a year after the discovery of the site of Harappa. Digging revealed that the mounds hid the remains of what once was part of a civilization that came up on the banks of the Indus River between 2500-1700 BC.

The mighty river breached its banks last month and caused unprecedented destruction in Pakistan.

The sites of the Indus Valley Civilization, among the most prized excavations of the Archaeological Survey of India, fell under Pakistan’s territory following the Partition of India in 1947.

The reports said that rainwater at Mohenjo-Daro “damaged excavated areas and exposed the ones buried underneath by creating furrows in them… the accumulated water seeped into the excavated areas, loosening the soil and resultantly tilting the walls.”

The Mohenjo-Daro town is about 3 km from the Indus River, from which the natives might have protected it using artificial barriers. They laid out these barriers with remarkable regularity into a dozen blocks, or “islands,” each about 1,260 feet (384 meters) from north to south and 750 feet (228 meters) from east to west, subdivided by straight or dog-legged lanes. While buildings on the high summit included an elaborate bath or tank surrounded by a veranda, a large residential structure, and a massive granary, the citadel functioned as the ceremonial headquarters of the site.