Sri Aurobindo at 150: How he stood against caste discrimination and a more inclusive Hinduism

(Written by Guru Prakash Paswan and Sudarshan Ramabadran)

Bengal has produced several seminal thinkers who have set up the foundations of our progress as a civilisational nation-state. Celebrating 75 years of Independence this year, India is taking nascent but steady steps towards enabling social cohesion and is contributing to enabling diversity, equity, and inclusion. Ramakrishna Paramahansa, Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, Jogendra Nath Mandal, Sri Aurobindo and Khudiram Bose, are some of the many revolutionary thinkers who continue to have an impact on Indian thought today, both nationally and globally.

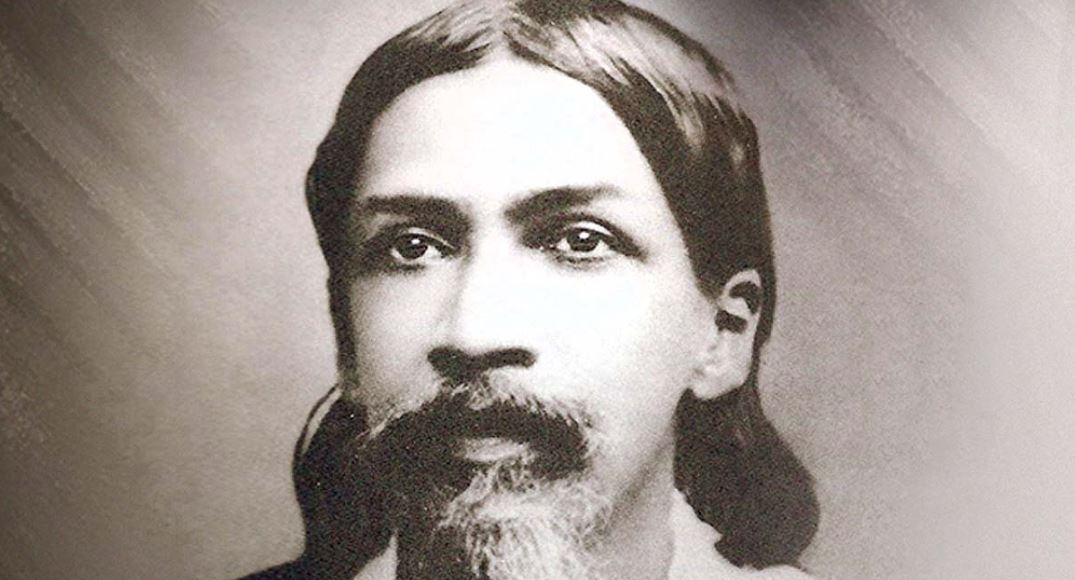

Aurobindo was a multifaceted personality. He was an original thinker, writer, poet, playwright, teacher and freedom fighter. He was a voracious reader who learnt the best of western philosophies and returned to India to create something uniquely Indian for spiritual transformation through his “integral yoga”. It is befitting that India is marking 150 years of his birth anniversary this year.

Aurobindo was inspired by the persona of Sri Krishna, the Yadava king, who was multifaceted — a king, diplomat, strategist, friend, advisor. Some of Aurobindo’s writings in Karmayogin, his weekly journal in English that he brought out after the Alipore Bomb Case, had Krishna and Arjuna in the Kurukshetra being pictorially represented on the cover. After being released in the Alipore Bomb Case, he was committed to his studies, and integral yoga. Aurobindo was also committed to taking forward the essence of the teachings of Krishna through his works, especially the Bhagavad Gita, amongst many others.

One perhaps under-analysed aspect of Aurobindo’s persona is his views on caste-based discrimination. Today, the ashram in Puducherry inspired by him does not cater to any man-made divisions. Perhaps the genesis of this was how Sri Aurobindo viewed the social evil of caste-based discrimination. This is discernible in some of his writings, Caste and Democracy, Un-Hindu Spirit of Caste Rigidity and Caste and Representation. These were written in 1907 for Bande Mataram, an English newspaper he edited then. A footnote is necessary because these were views of Aurobindo Ghose prior to his transformation, but it would be safe to say this continued to be his life-long guiding philosophy as Sri Aurobindo.

Sri Aurobindo was also inspired by Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak. His exchanges with Tilak set him on the path of revolutionary activity and to act against British rule and aspire for complete independence. However, this inspiration was not just restricted to revolutionary activities alone, but to the social fabric of the country. In the Un-Hindu Spirit of Caste Rigidity, Sri Aurobindo writes: “The Bengalee reports Srijut Bal Gangadhar Tilak to have made a definite pronouncement on the caste system. ‘The prevailing idea of social inequality is working immense evil’, says the Nationalist leader of the Deccan. This pronouncement is only natural from an earnest Hindu and a sincere Nationalist like Srijut Tilak.”

Aurobindo held all individuals as one and equal and this notion is for India to set before the world. He affirmed that education in India should be armed with the focus of the “Vedantic gospel of equality”. According to him, the British used caste as a political instrument.

Sri Aurobindo goes on to explain, “Nationalism is simply the passionate aspiration for the realisation of that Divine Unity in the nation… In the ideal of Nationalism which India will set before the world, there will be an essential equality between man and man, between caste and caste, between class and class.”

He also did not shy away from pointing out what the real problems were in “caste rigidity” and was committed to persuading everyone to remove all “unreasoning and arbitrary distinctions and inequalities”.

In and through these articles, Sri Aurobindo writes how caste in India is “peculiar” to our nation and the “spiritual vision of oneness” was lacking. He also states how caste-based discrimination was “accidental” and “external” and it furthered “social degradation”.

Sri Aurobindo also mentions examples of Chokhamela and Adi Shankaracharya to drive home to the reader his core point of accepting all as one and equal. He writes, “Chokhamela, the Maratha Pariah, became the guru of Brahmins, proud of their caste purity; the Chandala taught Shankaracharya: For the Brahman was revealed in the body of the Pariah and in the Chandala there was the utter presence of Shiva, the Almighty.”

Examples are galore in Indian history: Sri Ramanujacharya, whose teachings Aurobindo also mirrors foresaw, a thousand years ago, the unspoken aspirations of the downtrodden. All his life, Ramanujacharya stood for including the “outcaste” to make Hindu religion more holistic. According to B R Ambedkar, Ramanujacharya accepting a Dalit as his guru sent a strong message of social cohesion to society and the country at large. In fact, there is another connection between Ambedkar and Sri Aurobindo — Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III. The then ruler of Baroda (today Vadodara), helped Ambedkar study abroad at Columbia and Aurobindo get a suitable job at today’s MS University after his return from London.

In and through these important excerpts from his writings, it is clear that Sri Aurobindo was firmly against any man-made divisions, exclusion and “caste arrogance” based on birth. Social cohesion and a strong, united India were his goals. His 150th birth anniversary could be the best occasion to revive and relook at his teachings, read his works and strive towards a holistic, inclusive model that India can present to the world as he envisioned.

(Paswan is National Spokesperson of the BJP and Advisor, Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Sudarshan is author and researcher, currently studying at the University of Southern California. Both are writers of the book, Makers of Modern Dalit History. Views expressed are their own.)