Manas Dasgupta

NEW DELHI, Dec 7: The 1991 act for preserving the places of worship in India as they were on the day of Independence is in for a review. The Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna has constituted a Special Bench to hear petitions challenging the validity of the Places of Worship Act (Special Provisions) Act of 1991, which was enacted to protect the identity and character of religious sites as they existed on August 15, 1947.

The CJI Khanna headed bench would also include Justices Sanjay Kumar and K.V. Viswanathan and the bunch of petitions challenging the act is slated to be heard on December 12 at 3.30 p.m.

In March, 2021, a Bench headed by then CJI SA Bobde had sought the Centre’s response on the plea filed by advocate Ashwini Upadhyay challenging the validity of certain provisions of the law which even prohibited filing of a lawsuit to reclaim a place of worship or seek a change in its character from what prevailed on August 15, 1947.

The plea said, “The 1991 Act was enacted in the garb of ‘Public order’, which is a State subject (Schedule-7, List-II, Entry-1) and ‘places of pilgrimages within India’ is also State subject (Schedule-7, List-II, Entry-7). So, the Centre can’t enact the Law. Moreover, Article 13(2) prohibits the State to make a law to take away fundamental rights but the 1991 Act takes away the rights of Hindus, Jains, Buddhist, Sikhs, to restore their ‘places of worship and pilgrimages’, destroyed by barbaric invaders.”

It further added, “The Act excludes the birthplace of Lord Rama but includes the birthplace of Lord Krishna, though both are incarnations of Lord Vishnu, the creator and equally worshiped throughout the word, hence it is arbitrary.”

Muslim organisations like the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) and Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind however have countered that these petitions, in the guise of public interest petitions, cannot challenge a central legislation which had guarded the spirit of fraternity and secularism through protection of the religious character of religious places.

AIMPLB had pointed out that even the Ayodhya judgment had observed that the 1991 Act spoke “to our history and to the future of the nation… In preserving the character of places of public worship, the Parliament has mandated in no uncertain terms that history and its wrongs shall not be used as instruments to oppress the present and the future.”

The Gyanvapi mosque management has also sought to intervene in the case. The Committee of Management, Anjuman Intezamia Masajid Varanasi, which represents the Gyanvapi mosque, has argued that rhetorical claims and “purported grievances” caused by ancient rulers of the Mughal period cannot be grounds for challenging the validity of a legislative enactment like the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act.

The Gyanvapi Mosque committee has moved the Supreme Court, seeking the dismissal of the petitions a saying that consequences of declaring the 1991 Act unconstitutional are bound to be drastic and will obliterate the rule of law and communal harmony. It said an Article 32 petition challenging a legislative enactment must indicate the unconstitutionality of the provisions based on constitutional principles and the rhetorical arguments seeking a sort of retribution against the perceived acts of previous rulers cannot be made the basis for a constitutional challenge.

“The Parliament, in its wisdom, enacted the legislation as a recognition of secular values of the Constitution. The applicant humbly submits that while this Hon’ble Court considers this challenge to the 1991 Act, the petition may be dismissed as being devoid of merits,” the application added. It said that it was only after thorough deliberation and debate that the Parliament, in its wisdom and legislative competence, enacted the 1991 Act as a conscious decision to let the past not haunt the future of the country and the 1991 Act is a legislation recognising the preambular values of secularism and fraternity.

“Almost three decades from the enactment of the 1991 Act, the petitioner seeks to lay a challenge to the same by way of petition that is replete with rhetorical and communal claims which cannot be entertained by this Hon’ble Court,” the application stated.

It added that “the consequences of the declaration sought by the petitioner are bound to be drastic. As seen recently in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh where a court permitted a survey of the Shahi Jama Masjid by allowing an application for appointment of Survey Commissioner the very day when the suit was presented, in ex parte proceedings, the incident led to widespread violence and has claimed, as per reports, at least six citizens’ lives. The declaration sought by the petitioner would mean such disputes rising their head in every nook and corner of the country and ultimately obliterate the rule of law and communal harmony.”

The Managing Committee of the Gyanvapi Mosque has been made the subject of a litany of cleverly drafted suits filed seeking the right to have worship within the mosque, terming it as an old temple, said the application, adding that some of the suits seek removal of the mosque’s structure and for injunction against Muslims to use the mosque.

“However, a common thread that runs through all the cases is the said suits being under the interdict of Sections 3 & 4 of the 1991 Act. Therefore, the applicant is a crucial stakeholder in the challenge and seeks to assist this Hon’ble Court by way of the present intervention,” the application stated. Further, it said at present, as many as 20 suits were pending before different Varanasi courts seeking to nullify the protection accorded by the 1991 Act and to convert the character of the Gyanvapi Mosque and prevent access of Muslims to the mosque.

The Gyanvapi mosque is at the centre of multiple civil suits institutes by Hindu plaintiffs claiming the presence of a temple under the mosque and their right to worship. An authoritative decision by the Supreme Court would settle the fate of these civil suits by plaintiffs to “reclaim” ancient temples.

The Gynavapi mosque management had referred to how the Constitution Bench in the Ayodhya judgment had unequivocally held that the Supreme Court cannot entertain claims that stem from the actions of the Mughal rulers against Hindu places of worship in a court of law today. The Ramjanmabhoomi judgment had observed that “for any person who seeks solace or recourse against the actions of any number of ancient rulers, the law is not the answer.”

The Centre has however chosen to remain tight-lipped till date, promising to file a counter-affidavit in the pending challenge against the 1991 Act. The constitution of the Special Bench and listing of the case on a specific day has come amidst frenetic judicial interventions by local courts in States like Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh in the civil suits challenging the origins and character of mosques.

A Rajasthan court had issued notice to the Minority Affairs Ministry and Archaeological Survey of India in a suit filed by a Hindu organisation claiming “historical evidence” to prove that the Ajmer Sharif Dargah of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti was built over a Shiva temple.

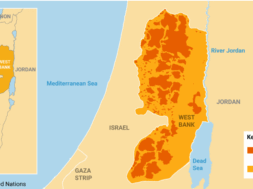

In Sambhal district of Uttar Pradesh, a civil court ex parte ordered a survey after a suit was filed claiming that the Shahi Jama Masjid at Chandausi was built by Mughal emperor Babar in 1526 after demolishing a temple. Violence and loss of lives had followed. The apex court had to step in with a caution to the district administration to maintain peace and harmony.

In August 2023, the apex court itself did not stop a local court order to have the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) continue with their “scientific investigation” of the Gyanvapi mosque premises at Varanasi, provided there was no excavation or damage to the structure. An earlier local court order for an advocate commissioner survey of the mosque had led to the discovery of a “shivling” in the mosque grounds.

The Muslim side had termed the civil suits followed by surveys conducted on premises of mosques as “salami tactics” of “one slice at a time.” Senior advocate Huzefa Ahmadi, who appears for the Muslim parties in Gyanvapi and Sambhal cases, had urged the court to flex the provisions of the Places of Worship Act to put a stop to such claims.