Same Sex Marriage Not Legalised nor Allowed to Adopt Child, But SC Tells Government to Protest Homosexuals against Harassment

Manas Dasgupta

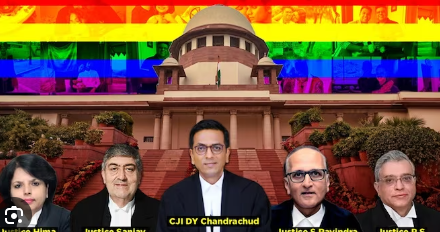

NEW DELHI, Oct 17: The Supreme Court on Tuesday refused to recognise same sex marriage and also rejected by a majority verdict the right of such couples to adopt children.

The five-judge constitution bench headed by the Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud nevertheless unanimously agreed that same sex couples face discrimination and harassment in their daily lives. The court urged the government to form a high-powered committee chaired by the Union Cabinet Secretary to expeditiously look into genuine practical concerns faced by same-sex partners such as getting ration cards, pension, gratuity and succession issues.

The centre had on May 3 told the court that it planned to form a committee headed by the cabinet secretary to explore administrative solution to problems faced by same-sex couples without delving into the marriage equality question.

The Chief Justice suggested that the committee should look into whether queer couples could be treated as members of the same family for the purpose of ration card; succession; maintenance; opening of a joint bank account; arrangement of last rites of partners; access benefits of rights and benefits of employment, etc.

The Court held that legalising same sex marriage would need framing of a new law which was not the job of court but Parliament and also refused to legalise the same sex marriage under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, which could open a Pandora’s Box in future.

A majority view on a five-judge Constitution Bench which decided the same sex marriage case that non-heterosexual couples cannot claim an unqualified right to marry. The bench stressed that an individual’s right to enter into a union cannot be restricted on the basis of sexual orientation. The five-judge bench came up with four judgments, differing primarily on the question of adoption rights for queer couples.

Though all five judges agreed that homosexuality was neither urban nor elitist concept as stated by the centre, they differed on the point whether the court can obligate the State to formally recognise the relationship of queer couples by giving it the legal status of a “civil union” or “marriage.

The minority views of Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul held that constitutional authorities should carve out a regulatory framework to recognise the civil union of adults in a same-sex relationship. The minority views of the two judges held that the right to enter into a union cannot be restricted on the basis of sexual orientation. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is violative of Article 15 of the Constitution, the Chief Justice said.

The majority views of Justices S.R. Bhat, Hima Kohli and P.S. Narasimha disagreed on the point, holding that it was for the legislature, and not the Court, to formally recognise and grant legal status to non-heterosexual relationships.

But all the five judges on the Bench agreed that the Special Marriage Act of 1954 was not unconstitutional for excluding same-sex marriages. They said tinkering with the Special Marriage Act of 1954 to bring same-sex unions within its ambit would not be advisable.

Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud concluded, in his opinion, that the court could neither strike down or read words into the Special Marriage Act to include same-sex members within the ambit of the 1954 law. Justice Kaul agreed that disturbing the Act, which facilitates inter-faith marriages, would have a cascading impact on other laws and the rights of others. The court was of the view that it was for Parliament and State legislature to enact laws on marriage.

In his opinion, Chief Justice Chandrachud said the relationship of marriage was not a static one. He held that queer persons have an equal right and freedom to enter into a “union”. He said the failure of the State to recognise the bouquet of entitlements which flow from a union would result in a disparate impact on queer couples, who cannot marry under the current legal regime.

Justice Kaul said heterosexual unions and non-heterosexual unions were two sides of the same coin. He said an “edifice” should be created to recognise the civil union of same sex partners and statutes should be interpreted in consonance with their right to enter into such unions. “Non-heterosexual unions are entitled to protection under a constitutional scheme… There is a necessity to recognise civil unions,” Justice Kaul said.

Justice Kaul observed that the legal recognition of such unions was a step forward towards “marriage equality.” “Practice of equality necessitates protection of individual choices. The capacity of same sex couples for love is no less worthy to protect than that of heterosexual couples,” Justice Kaul noted.

The view jointly authored by Justices S.R. Bhat and Hima Kohli, backed by a separate but concurring opinion by Justice P.S. Narasimha, said the court cannot give formal recognition to same-sex relationships by coining them as “civil unions”. The court cannot initiate the construction of a “parallel framework” of the institution of marriage. Such a recognition was not based on law.

Justice Bhat disagreed with the Chief Justice’s interpretation that the right to form a civil union by same sex couples flowed from their right to choose a partner, right to life and free expression. Justice Bhat said there was no fundamental right to marry. The right was regulated by enacted laws and legally enforceable customs. Framing a new code for legally recognised same-sex unions was the task of the legislature and not the court.

Justice Bhat said the court empathised with the desire of the LGBTQIA+ community for social acceptance and respect, but the means to arrive at that end must be legally sound, otherwise it may initiate untold consequences. “There is no unqualified right to marry except by statutes… the court cannot create a regulatory framework resulting in legal status,” Justices Bhat and Kohli held.

However, these limitations on providing a legal status to same-sex relationships did not preclude partners from “celebrating their commitment to each other in whichever way they wish within the social realm.” Justice Bhat held that the apex court’s judgment decriminalising homosexuality did not automatically extend to claiming legal entitlements or legal status to same-sex unions.

Justice Narasimha, in his opinion endorsing Justice Bhat’s views, said the right to marry was a statutory right and not a constitutional right as the Chief Justice had held. “The right to marry flows from legally enforceable customary practices,” Justice Narasimha said. He noted that a legally enforceable right to a civil union or legal status to an “abiding cohabitational relationship” by queer couples cannot be squeezed into the Fundamental Rights chapter of the Constitution.

The bench gave a 3-2 judgment on the question of adoption rights. Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud and Justice SK Kaul recognised the right of queer couples to adopt, while Justice SR Bhat, Justice PS Narasimha and Justice Hima Kohli disagreed. “There is a degree of agreement and a degree of disagreement on how far we have to go. I have dealt with the issue of judicial review and separation of powers,” CJI Chandrachud said.

Choosing a life partner is an integral part of choosing one’s course of life, the Chief Justice said. “Some may regard this as the most important decision of their life. This right goes to the root of the right to life and liberty under Article 21,” he said.

“The right to enter into union includes the right to choose one’s partner and the right to recognition of that union. A failure to recognise such associations will result in discrimination against queer couples,” the Chief Justice said, adding, “the right to enter into union cannot be restricted on the basis of sexual orientation”.

Disagreeing with the centre’s argument that marriage equality is an urban, elite concept, the Chief Justice said, “Queerness is not urban elite. Homosexuality or queerness is not an urban concept or restricted to the upper classes of the society.”

Supporting adoption rights for queer couples, he said there is nothing to probe that only heterosexual couples can provide stability to a child. “There is no material on record to prove that only a married heterosexual couple can provide stability to a child,” he said, adding that the Central Adoption Resource Authority “exceeded its authority” in barring adoption by same-sex couples. Justice Kaul agreed with the Chief Justice that there is a need for an anti-discrimination law.

“Same-sex relationships have been recognised from antiquity, not just for sexual activities but as relationships for emotional fulfilment. I have referred to certain Sufi traditions. I agree with the judgment of the Chief Justice. It is not res integra for a constitutional court to uphold the rights and the court has been guided by the constitutional morality and not social morality. These unions are to be recognised as a union to give partnership and love,” he said.

Justice Bhat agreed that queerness is “neither urban nor elitist”, but added that he does not agree with the Chief Justice’s directions. “The judgment of the Chief Justice propounded a theory of a unified thread of rights and how lack of recognition violated rights. However, when the law is silence, Article 19(1)(a) does not compel the State to enact a law to facilitate that expression,” he said.

Justice Bhat said the court cannot create a legal framework for queer couples and it is for the legislature to do as there are several aspects to be taken into consideration.

On the issue of adoption, Justice Bhat said they disagree with the Chief Justice on the right of queer couples to adopt. “We voice certain concerns. This is not to say that unmarried or non-heterosexual couples can’t be good parents… given the objective of section 57, the State as parens patriae has to explore all areas and to ensure all benefits reach the children at large in need of stable homes.”

Earlier, the Chief Justice disagreed with Justice Bhat’s approach. “My learned brother acknowledges the discrimination against the queer couples but does not issue directions. I cannot come to terms with such an approach.” The judges agreed that the court should not try to tweak the Special Marriage Act as it would amount to encroaching into the legislature’s domain.

Though the court has rejected the same sex marriage or right for adoption, but there was much to cheer about for the petitioners who were demanding equal rights for the queers. Besides that the bench’s refusal to legalise same-sex marriages was based not on an in-principle opposition to marriage equality but on legal technicalities and concerns of judicial legislation, it also agreed that difficulties faced by queer couples in accessing basic services are discriminatory in nature and said the government panel must look into them.

Several advocates of the petitioners agreed. “Even if the right to marriage has not been given, CJI has said the same bundle of rights which every married couple has should be available to same-sex couples,” one of the petitioners pointed out.

“Though at the end, the verdict was not in our favour but, so many observations made were in our favour. They have also put the responsibility on the central government. The Solicitor General said so many things against us, so it is important for us to go to our elected government, MPs and MLAs and tell them we are as different as two people. War is underway… it might take sometime but we will get societal equality,” said another petitioner.