Roving Periscope: No country wants Japan to release Fukushima waters in the Pacific Ocean

Virendra Pandit

New Delhi: Japan got a green signal from the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on Tuesday for its plans to pump out and release 1.3 million tons of treated radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean over the next few decades from the tsunami-wrecked Fukushima nuclear power plant, but no country wants Tokyo to go ahead with it.

Japan also needs to discharge the treated wastewater so the wrecked nuclear power plant could be decommissioned. The contaminated water has been distilled after it came in contact with fuel rods at the nuclear reactors 12 years ago.

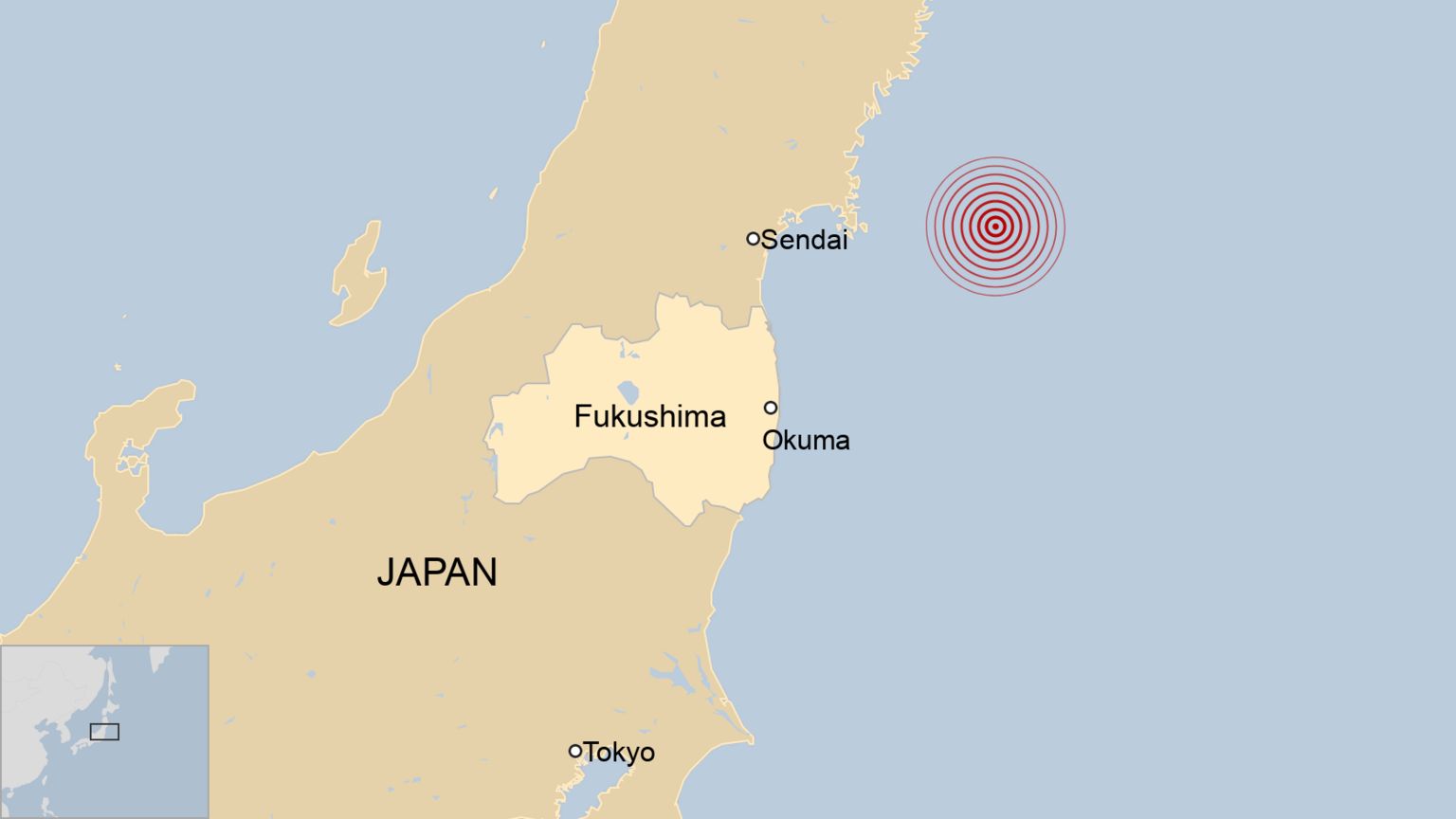

Tokyo said the process is safe as it has treated the water – enough to fill 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools – used to cool the fuel rods of the Fukushima nuclear power plant after it was damaged on March 11, 2011, when a 9.0-magnitude earthquake triggered a tsunami that flooded three Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant reactors.

Most of the controversial water comes from cooling the three destroyed reactors. The rest is from the rain that hit the contaminated site, and groundwater. Japan said it will release the treated water through a pipeline extending about one kilometer from the nuclear plant site into the Pacific Ocean, a process that can take over decades.

In particular, China, South Korea, and their neighboring countries fiercely resisted Japan’s attempts to release this water which they suspect is still radioactive and could harm their people’s health.

After a two-year review, the UN’s nuclear watchdog said Japan’s plans were consistent with global safety standards and that they would have a “negligible radiological impact on people and the environment.”

“This is a very special night,” IAEA chief Rafael Grossi told Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida before handing him a thick blue folder containing the final report, according to media reports on Wednesday. He called the report a “comprehensive, neutral, objective, scientifically sound evaluation.”

Japan has not specified a date to start the water release pending official approval from the national nuclear regulatory body for Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), whose final word on the plan, unveiled in 2021, could come this week.

Even Japanese fishing unions have long opposed the plan, saying it would undo work to repair reputations after several countries banned some Japanese food products after the 2011 disaster.

Japan said the water has been filtered to remove most radioactive elements except for tritium, an isotope of hydrogen that is difficult to separate from water. The treated water will be diluted to well below internationally approved levels of tritium before being released into the Pacific. It said the tritium levels in the treated water are lower than those found in wastewater regularly released by nuclear plants around the world, including in China.

China on Tuesday said Japan’s comparison of the tritium levels in the treated water and wastewater was “completely confusing concepts and misleading public opinion.”

With the tsunami damaging the Soviet-era electricity and cooling systems at the nuclear plant, it became the worst nuclear disaster in the world since the Chornobyl explosion on April 26, 1986, in Ukraine.

The nuclear plant produces 100 cubic meters of wastewater every day. As of now, about 1,000 water tanks on the contaminated site hold nearly 1.3 million cubic meters of water. However, they will reach their capacity in early 2024.

TEPCO has been filtering contaminated water to get rid of isotopes. The wastewater now contains only carbon 14 and tritium – a radioactive isotope of hydrogen – which are hard to separate from water. Still, TEPCO will dilute the water until tritium levels fall under the regulatory limit, the media reported.

Tritium does not emit enough radiation to penetrate human skin. But the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission said it can raise cancer risks if consumed in extremely large quantities.

Amid these controversies, fishers communities in Peru and Japan have expressed concerns that the released water could affect their livelihood.

Liliana Cornejo, the governor of Tacna Province in Southern Peru, raised questions about Tokyo’s assurance saying the water could still cause radioactive contamination. It will harm not only the ocean but all those who make their living from fishing along the coasts of Peru.

Fishing unions in Fukushima said the treated water is not a problem that ends after a single time or a year of release but lasts as long as 30-40 years, so nobody can predict what might happen.

On Tuesday, China again asked Japan to “stop pushing through the discharge plan”, and to “fully explore and evaluate the alternatives to ocean discharge to ensure that the nuclear-contaminated water is handled in a scientific, safe, and transparent manner.”

Amid food safety concerns, many South Koreans stocked up on sea salt before the wastewater discharge.

Following the 2011 nuclear disaster, South Korea banned seafood and agricultural produce from Fukushima due to safety fears. The ban continues despite a recent thaw in relations between the two countries.