Roving Periscope: Why did China ‘teach’ a lesson to India in 2020?

Virendra Pandit

New Delhi: A Chinese Communist Party strategist has sought to ‘explain’ why did China invade India in June 2020: New Delhi’s multiple ‘violations’ of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and related agreements.

But he failed to notice that this very Chinese act brought India closer than ever before to the West. And not just India. No other power player successfully united several of its enemies at such a breakneck speed as China did after the outbreak of Covid-19 in January 2020.

But this fact the Chinese expert conveniently overlooks. “In China’s view, the Galwan Valley incident is the inevitable result of India’s long-term violation of the 1993, 1996, and even 2005 and 2013 agreements,” Hu Shisheng, Director of the South Asia Institute of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), believes.

The bloody conflict claimed the lives of 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese troops, whose estimates run anywhere between 40 and 300.

But Hu’s claims do make an interesting read. For the first time since the Galwan River valley in Eastern Ladakh witnessed a fierce clash between the Indian Army and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), he sought to ‘justify’ the Chinese aggression.

He made these comments on the Chinese social media outlet, Weibo, while referring to the last week’s New Delhi visit of Defense Minister General Li Shangfu to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Defense Ministers’ conclave hosted by his Indian counterpart Minister Rajnath Singh.

This was the first visit by the Chinese Defense Minister after the PLA’s aggression in Galwan and five other areas along the LAC, the de facto bilateral border.

Hu’s Weibo post cited four reasons for China’s aggression:

- India took control of the Chumi Gyatse Waterfalls in the Dongzhang area in 1999. Locally known as the “Holy Waterfalls,” these comprise 108 waterfalls on the Sino-India LAC near Yangtse, one of the hotly disputed areas along the LAC;

- New Delhi scrapped Jammu and Kashmir’s special status in August 2019, abolished the Constitution’s Article 370, and divided the former state into two centrally ruled Union territories: Ladakh and J&K;

- The alleged “aggression” displayed by the Indian military patrols since early 2020. These patrols were becoming unduly aggressive, “building bridges and roads, and continuously extending the patrol route;” and,

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi “violated” the 1988 agreement in Beijing between then PM Rajiv Gandhi and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping to put the border dispute on the back burner and develop other aspects of the bilateral relationship.

Hu claimed that PM Modi had ‘hijacked’ the border issue by making it a central piece of bilateral relations.

“As a result, it will be difficult for China-India relations to get out of the sluggish state of ‘three deficiencies,’ that is, lack of forward momentum, lack of normal cooperation, and lack of strategic mutual trust.”

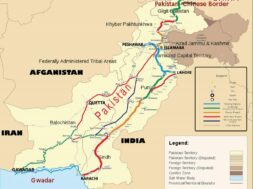

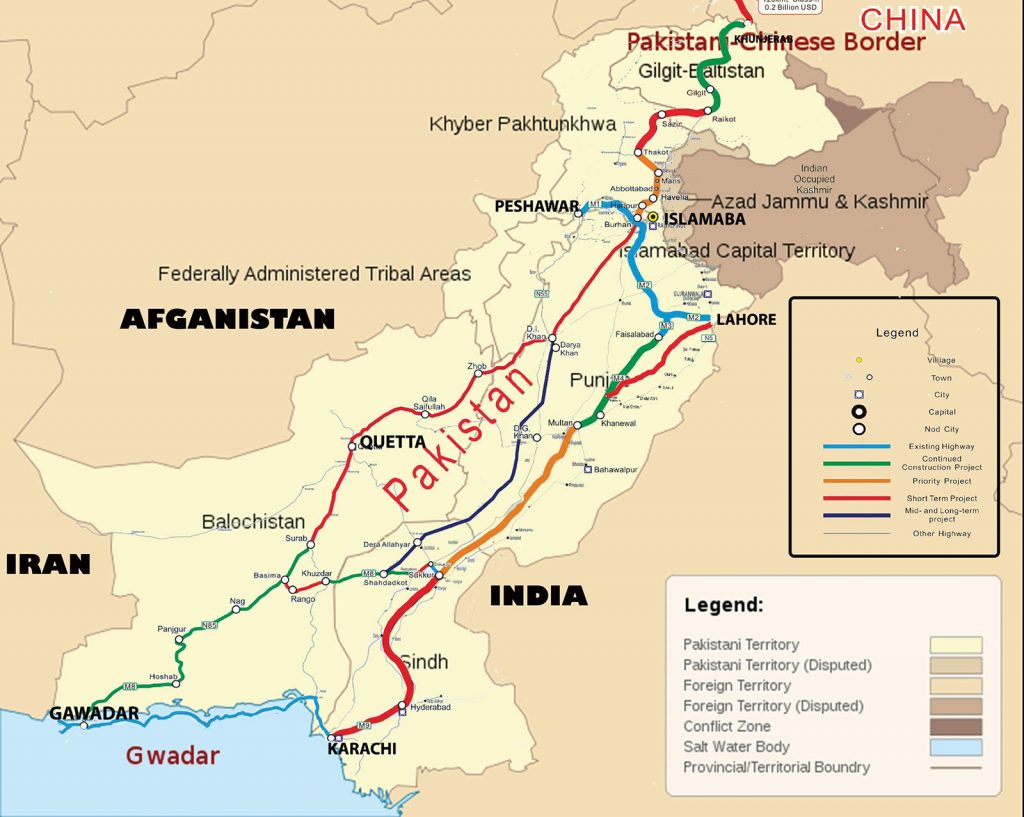

But Hu did not mention the key reason: China’s apprehension that a rising and stronger India, having already brought J&K under the central rule, could reclaim Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK) and jeopardize the USD 60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which passes through the Gilgit-Baltistan region.

The territorial dispute between China and India involves three sectors of the LAC—the eastern sector in Arunachal Pradesh, which extends about 90,000 square kilometers; the central sector, near Nepal, of 3,000 square kilometers; and the western sector, in Ladakh, which measures 33,000 square kilometers.

But even in 1962, China manufactured ‘reasons’ for invading India to ‘teach’ it a lesson without exactly getting the desired results. These reasons were:

- To show its displeasure with India for hosting the Dalai Lama who fled Tibet in 1959 when the People’s Republican Army attacked and seized Tibet;

- To free itself of Soviet influence and convey to Moscow that Beijing (then Peking) ignored Russia’s leadership of the global Communist Movement. China was also concerned about Russia helping India to set up steel plants etc. Soon after this invasion, therefore, Beijing engineered a split in the Communist Party of India (CPI) and nursed the breakaway CPI (Marxist) to toe the Chinese line. But it increasingly pushed New Delhi closer to Moscow; and,

- To force India to submit to Chinese hegemony. But even this tactic failed when India defeated the Chinese protége Pakistan in 1965 in a key war.

According to the US-based Chinese academic, Yun Su, tactically, China wanted to put an end to the infrastructure arms race along the border, but strategically it was in no hurry to resolve the disputes as it bogs India down as a continental power.”

This also makes sense. For instance, in the 18 rounds of military commanders’ talks after the 2020 conflict, China has hardly shifted its position.

After PM Modi came to power in 2014, India has been trying to change the status quo of the preceding governments. Its road-building units were building and improving border roads that provided and improved connectivity between places on the Indian side of the LAC, including the so-called Darbuk–Shyok–Daulet Beg Oldi (DSDBO) road that connected up with India’s northernmost posts at the foot of the Karakoram Pass.

One more reason for the Chinese aggression in 2020 was to keep India engaged in saving its own skin while Beijing tries a shot at Taiwan!