Virendra Pandit

New Delhi: Eighty percent of agricultural land irrigation in Pakistan depends entirely on water from the Indus River system, an Australian think tank has said.

Australia’s Sydney-based nonprofit Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), one of the world’s most respected think tanks, just dropped a ‘water bomb’ Pakistan has been fearing for months. Its “Ecological Threat Report 2025” has revealed that India now possesses the technical capability to alter the flow of the Indus River and Pakistan is powerless to stop it, the media reported on Saturday.

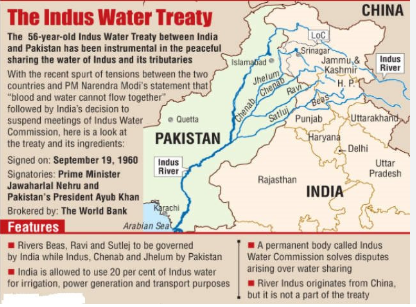

Strongly reacting to Pakistan-based terrorists killing 26 innocent tourists in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir, in April this year, India suspended the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) that guaranteed water supply to Pakistan for over six decades.

Since April, Pakistan has been facing acute risks of water shortages as India has the ability to change the flow of the Indus River within its technical capacity.

Afghanistan can also complicate matters for Pakistan. Earlier this week, Kabul moved to curb Islamabad’s access to water from cross-border rivers. The Taliban said that Kabul will build a dam on the Kunar River as soon as possible.

By holding the treaty in abeyance, India is currently not bound by its water-sharing obligations under the IWT. In 1960, New Delhi consented to share the waters of the western rivers, the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab, with Pakistan, while retaining control over the eastern rivers, including the Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej, for its own use.

While India cannot completely stop or divert the flow of water, the report noted that even minor adjustments in dam operations at critical times, like summers, could significantly impact Pakistan’s densely populated plains, especially in Punjab and Sindh.

The report warns that Pakistan’s storage capacity is limited to roughly 30 days of river flow, making it vulnerable to seasonal shortages. Any disruption to the river water flow, can lead to immediate and catastrophic water shortages that could trigger famines, economic collapse, and mass migration.

In May, India conducted reservoir flushing at the Salal and Baglihar dams on the Chenab River without notifying Pakistan. This caused a flood-like situation along the Chenab in Pakistan, demonstrating the strategic leverage New Delhi held over river management after the suspension of the IWT.

Earlier this week, Afghanistan also expedited its plan to build a dam on the Kunar River, curbing Pakistan’s access to the cross-border water body.

Pakistan’s farmers are already facing a relentless struggle against climate change, and are fighting floods and droughts alternately.

The Indus River originates in Tibet near Lake Mansarovar, flows northwest into Ladakh, then enters Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir, traverses the length of the Muslim nation from north to south, and drains into the Arabian Sea near Karachi. Pakistan lacks sufficient dam storage to buffer variations in river flow.

The IEP report revealed that even small disruptions, if timed poorly, can severely affect agriculture.

“For Pakistan, the danger is acute. If India were truly to cut off or significantly reduce Indus flows, Pakistan’s densely populated plains would face severe water shortages, especially in winter and dry seasons,” noted the report.

India’s dams on the western rivers are primarily run-of-the-river projects, as mandated by the IWT. These dams have minimal storage. This means New Delhi cannot completely stop river flows.

However, the timing and regulation of dam gates gives India considerable influence over downstream conditions, placing Pakistan in a strategically vulnerable situation.

The report also noted that India, not bound now by the IWT emptied dam reservoirs to remove silt on the Chenab in May without consultation with Pakistan. Sediment accumulated at the bottom of dams is typically removed every 5–10 years or as needed, using methods like dredging or sluicing.

“India proceeded unilaterally, aiming to boost its dams’ storage and power generation capacity now that it considers itself unbound by IWT limits. The immediate impact was dramatic: sections of the Chenab in Pakistan’s Punjab ran dry for a few days, as India’s dam gates were shut, then released sediment-laden torrents when opened,” it noted.

The IEP report said that the IWT shifted from a framework of cooperation to a source of growing contention, which reflected deterioration in India-Pakistan relations. For decades, India had not fully utilised the water allocated to it under the treaty, with significant flows of the Ravi and Sutlej (eastern rivers) continuing to run unused into Pakistan.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, India launched a concerted effort to harness its full share. Projects like the Shahpurkandi Dam on the Ravi (completed in 2024) and the Ujh Dam on a Ravi tributary were built to divert remaining waters for Indian use. Simultaneously, India accelerated hydropower development on the western rivers, like Ramganga and Kishanganga, carefully staying within the IWT limits.

The report makes it clear that Pakistan’s water security is increasingly at the mercy of India’s strategic decisions. With limited storage and rising tensions, even small changes in river flows could have catastrophic effects on its agriculture and food supply.

And, India doesn’t need to completely stop the water flow to bring Pakistan to its knees. The Australian report revealed that even minor adjustments to dam operations during critical periods, like summer, could devastate Pakistan’s agricultural heartland.

The report detailed how this situation has already begun unfolding. After India suspended the IWT, it released water from the Chenab River without consulting Pakistan. Initially, parts of the river ran completely dry, but when India later opened the gates, a surge of silt-filled, turbulent water rushed downstream, wreaking havoc as Pakistan watched helplessly.