Virendra Pandit

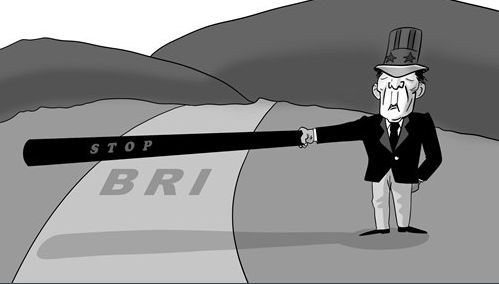

New Delhi: It was no secret even before the Covid-19 pandemic hit the world in January 2020 that the planet’s biggest-ever infrastructure project, worth USD 200 billion—China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—was facing rough weather. Now, this gargantuan dream project of China’s President-for-Life Xi Jinping is almost crashing down for want of funds.

Even the BRI’s flagship project, the USD 60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), is facing severe problems in Baluchistan where terrorists have killed or wounded many Chinese workers in recent months and the locals are protesting for a month demanding the return of their lost livelihoods and promises.

Since 2019, investments in the much-publicized BRI have plummeted by a whopping 54 percent and Beijing is no longer able to fund projects in Africa, amid criticism over infrastructure debt-traps and loan defaults, a think-tank said.

When he came to power in 2013, Xi Jinping launched the BRI as the start of his crowning glory with much fanfare. It purportedly aimed to link Southeast Asia, Central Asia, the Gulf region, Africa, and Europe with a network of land and sea commercial routes. Under the BRI, China undertook big infrastructure projects in the world which in turn would also enhance Beijing’s global influence. Many countries signed up but either backed out or sought revision in terms and conditions when they realized how Beijing had debt-trapped them.

The media reports quoting China-based think-tank Green BRI, which analyses the global infrastructure initiative, the BRI investments last year were at their lowest since they unveiled the program in 2013. The BRI has seen its investments in the 138 participating countries slide 54 percent from 2019 to USD 47 billion last year, it said.

Doubts about the deals, the global suspicion about China’s intentions after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Dragon’s own falling economy contributed to the fall. It forced Beijing to be more cautious about the development of overseas projects, the media reported on Monday.

Once bitten twice shy, Beijing is trying to rebrand the BRI after US President Joe Biden launched a rival network, the Build Back Better World (B3W), during the June G-7 summit, with the goal of creating “a values-driven, high-standard and transparent infrastructure partnership”. It aims to help finance projects in developing countries. The European Union too has recently launched a USD 340 billion new Global Gateway initiative to compete with the BRI.

In Africa, where the Dragon expanded its influence with massive investments since 2013, Beijing stopped funding projects in debt-ridden Africa amid Covid-19 disruptions, and there was little hope for quick returns.

In the last month’s Eighth Ministerial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), President Xi offered fresh incentives, including a billion Covid-19 vaccines, waiver of debt, and creation of eight lakh jobs. But he did not offer big cash incentives as he did in the past.

Unlike in 2018, for instance, at FOCAC in Beijing, Xi promised USD 15 billion in grants and interest-free loans out of the total USD 60 billion in financing offered by China. This time around, there was no promise at all.

An official paper on China-Africa cooperation said 45 percent of the RMB 270 billion (USD 42 billion) of China’s foreign aid from 2013 to 2018 went to African countries in the form of grants, interest-free loans, and concessional loans, in return for Beijing-friendly measures.

From 2000 to 2020, China helped African countries build over 13,000 km of roads and railways, over 80 large-scale power facilities, funded at least 130 medical facilities, 45 sports venues, 170 schools, and built the African Union Conference Centre.

China was also reacting to pressure, as African civic groups, trade unions, and environmentalists became increasingly critical of major Chinese-financed infrastructure deals.

Last month, Xi cautioned Chinese officials that the global environment for BRI is getting increasingly complex, and asked them to maintain strategic determination, seize strategic opportunities, actively respond to challenges, and move forward.

China had officially invested USD 139.8 billion by 2020 in BRI projects, including USD 22.5 billion last year. This includes the BRI’s flagship CPEC in which Beijing has so far invested over USD 25 billion, out of USD 60 billion.

The CPEC itself passes through the disputed area. India has protested to China over the 3.000-km long CPEC connecting China’s Xinjiang with Pakistan’s Gwadar Port as it is being laid through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK).

Lack of transparency of the BRI agreements and mounting debt to China by smaller countries have raised global concerns.

For example, the 99-year lease of Hambantota port to China by Sri Lanka has raised red flags about the downside of the BRI and Beijing’s push for major infrastructure projects costing billions of dollars in small countries.