Jayesh. Purohit

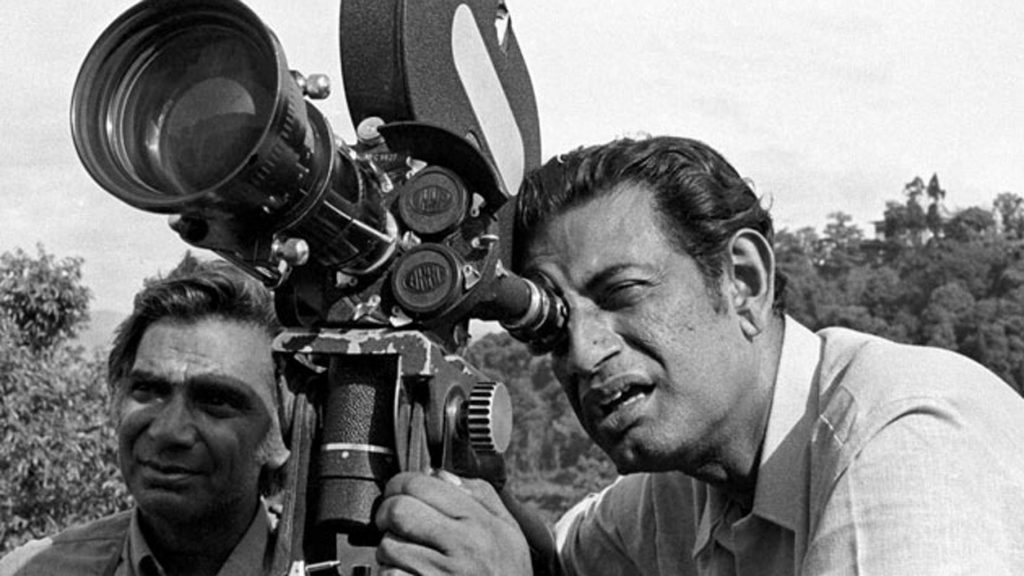

On the birth centenary of legendary film-maker Satyajit Ray, here are my thoughts on how this genius infused new hope in my life when I was passing through a depressive phase of my teenage years. At the same time, Mr Ray’s achievement brought fresh enthusiasm in India and Indian cinema when both were struggling with crises – economic and artistic. The article explores Ray’s idea of dialogues in movies and how camera can challenge and outweigh the role of a script & dialogue writer.

The ‘Ray’ of Hope For Me and Indian Cinema

Relocation is always painful for me. That was 1991 when we shifted our base from riots-ridden Gomtipur to a peaceful Nava Vadaj, where I never found peace of mind. Even after spending a year at a newly purchased house, I failed to befriend anyone with whom I could match my wavelength. The school hardly gave me any respite as my academics deteriorated from above average to below average. This was something beyond my understanding; I was going through a magical transmogrification. Earlier, I used to be a carefree, spirited adolescent, who wouldn’t give a damn to serious stuff. At a new place, I became a grave adult although in my teens.

It took more than a year to get acclimatized with the new postal index number that ends with ominous 13. But a sort of miracle occurred in late March 1992, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences conferred Lifetime Achievement Award on Mr Satyajit Ray. He was the first Indian to receive an Honorary Academy Award and this brought a litany of commendations from all corners. For that week, Ray was the darling of Indian media. Our household, which always has high regard for film makers and people associated with films, was all cheerful about this phenomenal accomplishment of Ray. Although we were (and are) not connected with this maestro of celluloid, we were delighted with his artistic feat, for which India garnered global recognition.

For an 11th grader, this was something unusual yet mesmerizing. Unusual because of my little knowledge and understanding of Academy Awards and their value; mesmerizing because I have always regarded films as a strong tool of mass communication. One might wonder how a school-going kid in his boyhood can measure the influence of movies as mass comm device. Trust my words, before celebrating my 16th birthday, I had relished meaningful movies like Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), Gandhi (1982), Awara (1951), Guide (1966) and the like.

Following that week, my life changed for good. Films, literature, advertising, language and other disciplines of humanities began to influence me and shape my thoughts. During my graduation, Professor B C Dalal would talk elaborately on films in general and Mr Ray in particular. While studying literature at Gujarat University, respect for the film-maker was taken place by veneration; I began to see in awe at his achievements.

In later years, during my career as commercial writer, I marauded Internet to search about known and unknown film makers of India. Mr Ray would always lead the list as I scroll the pages of Wikipedia and other websites to read about films and their makers. In my heart of hearts, I liked the fact that in the beginning of his career, Mr Ray was working in an advertising agency. It gave me a psychological high to know that my career interests match with many great artists, who have worked in the area of advertising; the others include Shyam Benegal, Salman Rushdie, R. Balakrishnan, Gauri Shinde, and Nitesh Tiwari. So for once, I thought I had a great opportunity to show my mettle in advertising and then in moviedom.

Critics On Ray’s Films

Satyajit Ray’s contribution to Indian cinema has received mixed reviews from film critics. While there are many who appreciate his movies for the questions they raised and treatment he gave, a few censure his films as documentaries. Slow pace of the narration can be one of the reasons why his movies are compared with documentaries. However, the argument is far from reality. A careful scrutiny of his creations reveals a different story.

That a film is a visual story is known to all. Ray knew how to get the most out of his camera. And when the camera is in action, there is little left to the dialogues. The job of a dialogue writer in Ray’s movies is more challenging. Because, s/he has to use his/her fine judgement to decide when to put dialogues into the mouths of characters and when camera should be allowed to speak.

According to Ray, “The role of dialogue in a film is twofold. First, it explains the story. Second, it describes various characters in the film. The same function that words perform in literature is performed together by images and words in a film. Words are not needed to describe a scene; images can do that job. When it comes to describing the physical attributes ofa character, again images can handle that. It is the nature of the character that comes across partly through the expression and gestures made by an actor and the rest by words he or she speaks.“

He further suggests, “One ought to try to convey through words only what images cannot capture.“

Here, images mean camera. So when camera fails to describe the scene, dialogues should pitch in. For Ray, his characters are not just the puppets in the hands of a director as they have to play a vital role using their body language in the absence of dialogues. It seems that Ray had a remarkable dislike for dialogues in films. He said, “Words are all-important in a play, not in a film.“

A movie is a drama enacted on celluloid, and therefore, camera has a bigger responsibility to dramatize the movie. A play, when performed in theatres, does not have this luxury, and therefore, dialogues have to have visual effects on the minds of spectators. Probably for this reason, some critics were under the impression that Ray’s movies bordering on documentaries.

Natural and Realistic Dialogues

Another reason why critics berate Ray is his penchant for natural and realistic dialogues be used in movies. This allows little space to dramatise situations. Thus, a scriptwriter is always walking on tightropes of “extraordinary observation” and “remarkable memory”. There is no scope for writers to use their own experiences and imagination as Ray believed that “The writer should forget his own identity completely, enter the character he is describing and, through the use of dialogue, bring that character to life.“

Ray’s over-dependence on real life makes his movies bland for common theatre-goers. Not all viewers can understand the silent language of camera; for them, dialogues are an easy source to connect with what is happening on screen.

A multi-faceted diamond

A multi-dimensional personality, Ray was a prolific writer, publisher, illustrator, calligrapher, music composer, graphic designer, and film critic. As a writer, he has immensely contributed to Bengali literature in the form of short stories and novels for young children and teenagers. His book ‘Speaking About Films’ is a compilation of articles translated by Gopa Majumdar, reveals two fascinating dimensions of Ray’s personality – creator and critic.

Unlike many of his contemporaries in India and abroad, Ray successfully theorised and lectured his ideas, process of creativity, and innovations on making films. The only one who had done this was Sergei Eisenstein, who described his own creative process at length. However, Eisenstein could produce only seven movies during his career spanning more than twenty years.

Ray was not just a craftsman, who would use tools and devices to create successful movies; he was very much aware of his own creativity. There was a creator and a critic living inside a single brain. So if you ask him about the idea for a particularly felicitous touch in his films, he, unlike John Ford, wouldn’t say, “Aw, I don’t know, it just came to me.” He can furnish countless reasons why he developed certain characters, how inevitable some scenes were in his movies, and what inspired him to create masterpieces.

Satyajit Ray believed “One quality which is sure to be found in a great work of cinema is the revelation of large truths in small details. The world reflected in a dewdrop will serve as a metaphor for this quality.“ For such a great artist, a single article is not enough; he was and will always remain an ocean of creativity and the ocean cannot be reflected in a dewdrop.

The parasol of world cinema, under his shade generations will flourish, Ray will be the ’Ray of Hope’ for the entire film fraternity as once he was for me. Happy Birthday to the luminary of Indian Cinema.

About the Author

Jayesh Purohit is a writer. Alphabets create the same impact on him as cheese would create on Jerry the Mouse. His romance with words dates back to the twilight years of 20th century when he lost his heart to Miss British Lingo. He loves to write on Literature, Language, Advertising, Branding, and Entertainment.

(Sanket)