Manas Dasgupta

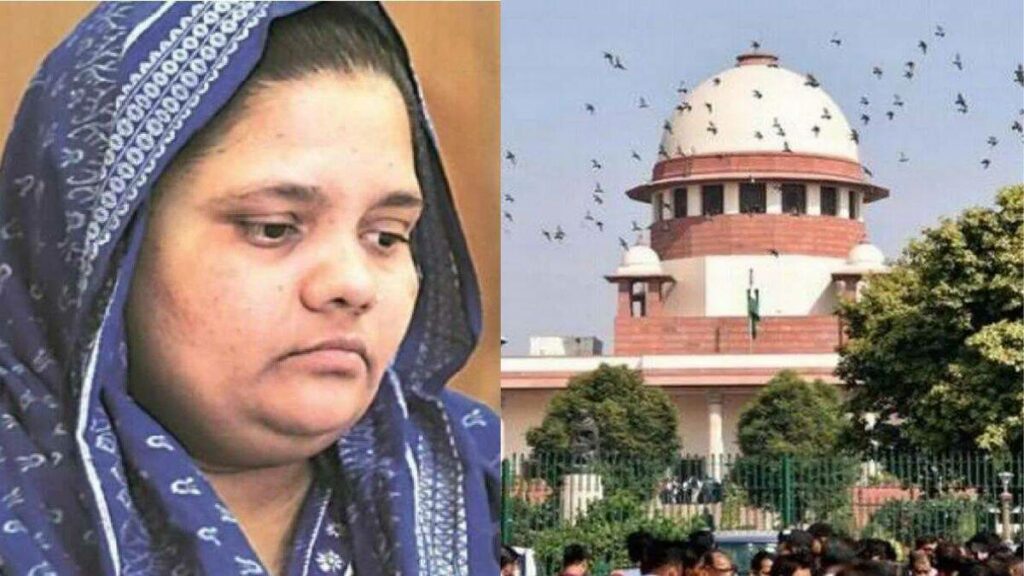

NEW DELHI, Dec 17: The Supreme Court on Saturday dismissed one of the two review petitions filed by a victim of the 2002 Gujarat riots challenging the premature release by the state government of 11 convicts serving life imprisonment for gang raping and murder of 14 persons including seven family members of Bano.

In the dismissed request, she’d had asked the court to review its May 2022 order that told the Gujarat government to consider the convicts’ release plea. Her other case, which challenges the very grounds of the release, however, is not immediately affected by this decision. A detailed order was not immediately available.

As for Ms Bano’s other petition challenging the very decision of the Gujarat government, it was adjourned last week as one of the judges, Justice Bela Trivedi, withdrew from the case. She did not specify why. The petition has been returned to the Chief Justice of India for referring it to some other bench.

The 11 convicts serving life term walked out of jail on August 15 as they were granted premature release – on account of “good behaviour” – under a 1992 policy by Gujarat’s BJP government with a nod from the Union Home Ministry.

A Bench of Justices Ajay Rastogi and Vikram Nath dismissed Ms. Bano’s review petition by circulation in the chambers. Her petition had wanted the court to reconsider its judgment which permitted the Gujarat government to apply the State’s Premature Release Policy of 1992 while deciding pleas made by the 11 convicts for early release.

In its May 13 judgment, a Bench led by Justice Rastogi had concluded that Gujarat was the “appropriate government” under Section 432 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to decide the remission of the convicts in the case. The latest policy says gang rape and murder convicts cannot be grated early release, but the Supreme Court had agreed with the argument that the 1992 policy, which had no such exception, applied to these men. That 1992 policy was, technically, in effect when the men were convicted in 2008.

Challenging this, Bilkis Bano had also argued that Gujarat was not the right state to take a decision as the trial was held in neighbouring Maharashtra. The trial had been moved to Mumbai on the Supreme Court’s instructions in 2004 after Ms Bano said a fair trial could not be held in Gujarat.

Others like CPI (M) leader Subhashini Ali and others like TMC leader Mahua Moitra have also challenged the early release of the convicts in separate writ petitions. Their petitions were last heard by Justice Rastogi’s Bench on October 18. The court had then given petitioners time to respond to a Gujarat government affidavit which showed that the Special Judge and the CBI in Mumbai had opposed the premature release of the 11 convicts.

The affidavit by the State of Gujarat had revealed that while the Superintendent of Police, CBI, Special Crime Branch, Mumbai and the Special Judge (CBI) of Greater Bombay opposed the premature release all the authorities in Gujarat and the Home Ministry recommended their release.

“All the prisoners have completed 14 plus years in the prison under life imprisonment and opinions of the authorities concerned have been obtained as per the premature release policy of 1992 and submitted to the Ministry of Home Affairs vide letter dated June 28, 2022 and sought the approval of the Government of India. The Government of India conveyed the concurrence/approval of the Central government under Section 435 of the Code of Criminal Procedure for premature release of 11 prisoners in a letter on July 11, 2022,” the 57-page affidavit had said.

Hearing a plea by one of the convicts in the case, Radheshyam Bhagwandas Shah, the Supreme Court had on May 13 this year asked the Gujarat government to decide within two months, his application seeking “premature” release from prison, where he had spent more than 15 years following conviction in January 2008.

The ruling relied on the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in State of Haryana Vs. Jagdish where it had said “the application for grant of premature release will have to be considered on the basis of the policy which stood on the date of conviction” and accordingly held that the “policy (for remission) with which the petitioner has to be governed, applicable in the State of Gujarat on the date of conviction, indeed is” the one “dated 9th July 1992”.

In her review petition, Bano said the convict on whose plea the Supreme Court had given the May 13 order had not made her party in his plea and as a result, she had absolutely no information of the filing or pendency of his petition and the court order following which the state government took the decision to release the 11 convicts.

Contending that the Gujarat government’s decision to release them early suffers from non-application of mind, she said the convict had withheld “relevant facts and aspects of vital importance” from the Supreme Court, including the nature of the crime and her name.

After the men had served about 15 years in jail, one of them went to court asking to be considered for premature release as per the policy for lifers. That contention reached the Supreme Court, which told the Gujarat government in May this year that these should be considered.

Less than three months later, the men walked free and have since settled back into their lives. One of them even campaigned for his daughter who became a BJP MLA in this month’s elections that consolidated the party’s hold on power.

Several judgments of the Supreme Court, most recently in April this year, have underscored that a State cannot exercise its remission powers arbitrarily. The court, in State of Haryana versus Mohinder Singh, had held that the grant of remission should be “informed, fair and reasonable.” In Rajan versus Home Secretary, Department of Tamil Nadu, the top court had held that “grant of premature release is not a matter of privilege but is the power coupled with duty conferred on the appropriate government.”

The court had in Laxman Naskar versus Union of India laid down five questions which should feature in the State’s mind before deciding on remission. These include whether the offence is an individual act of crime that does not affect the society; whether there is a chance of the crime being repeated in future; whether the convict has lost the potentiality to commit crime; whether any purpose is being served in keeping the convict in prison; and socio-economic conditions of the convict’s family.