Manas Dasgupta

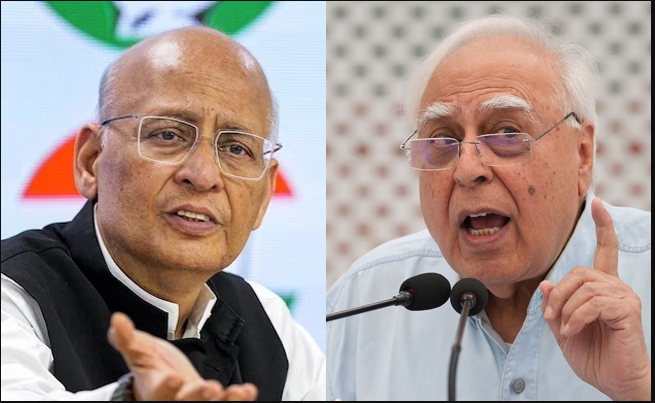

NEW DELHI, Nov 27: Senior Advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi on Thursday questioned the powers of the Election Commission of India (ECI) to order Special Intensive Revision” (SIR) en masse and claimed that under the Representation of the People Act (ROPA), its powers to conduct SIR was limited to a constituency and not an entire state.

The Supreme Court is currently hearing pleas challenging the SIR exercise of electoral rolls in various states and union territories in the country. The Supreme Court has said the argument that the special intensive revision of electoral rolls was never conducted before in the country cannot be used to examine the validity of the Election Commission’s decisions to carry out this exercise in several states.

Mr Singhvi argued that the ECI can assess citizenship under Article 326, but only if somebody raises an objection to the inclusion of a name in an application made under Form 7 of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960. Otherwise, there are two laws — the Foreigners Act and the Citizenship Act — which govern the issue of illegal immigrants, he says. He wondered that if one loses his right to vote because he could not submit the parents’ records as voters, “it is a serious issue.”

“Your Lordships have spent months giving the healing touch, and in the process, we have forgotten the law. SIR is limited to a constituency or a small group, not en masse. Parliament had decided the limits,” Mr Singhvi said. He argued that the power of ECI under Section 21(3) of ROPA to “direct a special revision of the electoral roll for any constituency or part of a constituency in such manner as it may think fit” cannot be interpreted as an en masse exercise.

“There is a different procedure if a dead person is still found in the voter list. But here it is an en masse exercise which imagines a huge, marauding influx into India. Crores and crores of people, State after State, are being asked to prove their citizenship. Where is the ECI’s jurisdiction to do this? Article 324 cannot be used to plug holes in the ECI’s jurisdiction,” said Mr Singhvi.

He said the ECI was making substantive changes in the guise of making procedural corrections. “Substantive changes in the law can only be made by the Parliament,” he argued. “Can the ECI, in June 2025, bring out a form to which 11 or 12 documents have to be annexed? Where is the parliamentary law or rule that authorises the ECI to do that? “

According to him, “Article 327 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to make laws for elections. That is the Representation of the People Act (ROPA). The ROPA only includes Forms 4, 6, and 7. The Election Commission (ECI) cannot devise its own forms (enumeration forms) and cannot assume powers de hors (other than) what is provided in ROPA,” said Mr Singhvi.

Another senior advocate appearing for the petitioners Kapil Sibal pointed out that “The ECI is supplanting the entire procedure for revision. They are introducing enumeration forms and shifting the burden of proof of citizenship, placing it on citizens in the same way it is on foreigners. How will I discharge the burden when my father has not voted in the 2003 roll or he died before that?” argues Kapil Sibal.

“The exclusionary conditions that existed before Independence are now existing after Independence,” he said. “Whether a person is an Indian citizen or not is decided by the MHA. Whether a person is of unsound mind is determined by a competent court. Laws such as the Prevention of Corruption Act and the Representation of the People Act form the statutory basis for disqualifying a person from the electoral roll. You cannot ask the BLO to decide all this,” Mr Sibal argued, referring to Section 16 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950.

He also said it was “a dangerous proposition and unreasonable, both substantively and procedurally, to have a school teacher deployed as a BLO to determine citizenship.” He referred to Section 3 of the Citizenship Act and discussed the acquisition of Indian citizenship. He pointed out how citizenship was granted to persons whose one parent is a citizen of India, while the other is not an illegal migrant at the time of their birth. “How will this person prove that their parent is not an illegal immigrant now?” Mr Sibal asked.

Referring to Section 19 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, which lists the conditions for registration in an electoral roll, Mr Sibal said there were only two conditions laid down to become a voter, a person must be 18 years old and ordinarily resident in a constituency. Mr Sibal stated that Aadhaar can be used to verify these two details. A Booth Level Officer (BLO) need only look at these two factors, he did not have the authority to determine a person’s citizenship as there were other authorities for that purpose, he added.

Meanwhile, reports said Tamil Nadu’s SIR exercise has turned chaotic, risking the deletion of lakhs of genuine voters ahead of next year’s elections. From unrealistic deadlines to confusing forms and missing instructions, the process is breaking down on the ground, it added.